Plus: Tickle Me Elmo and end user demand; Why do all shortages end in gluts? And who is TSMC's customers' customers' customer?

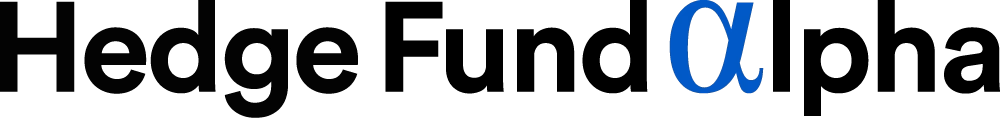

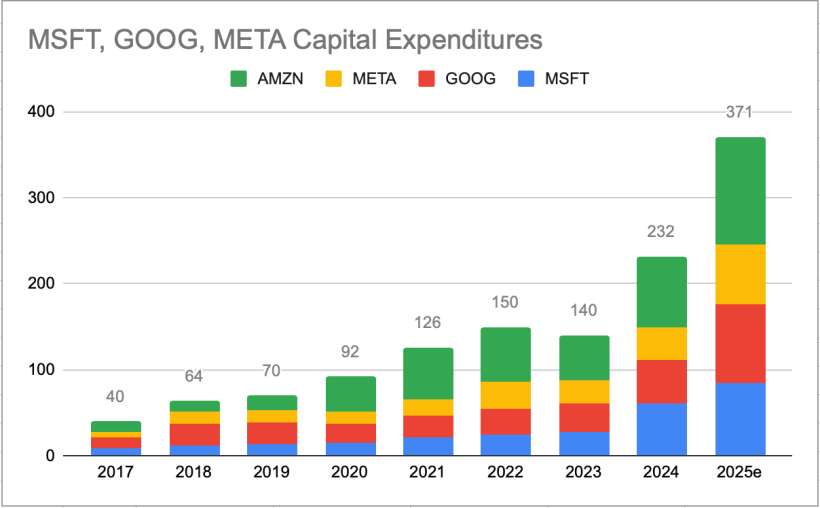

Two years ago, I wrote a post about the rising capital intensity of big tech and the depreciation charges that would soon flow through income statements. This continues to be my valuation concern, as free cash flow lags net income significantly. Big tech stocks might look reasonably valued on a P/E basis but they are quite expensive on a P/FCF basis:

TTM numbers; FCF counts stock based comp as expense

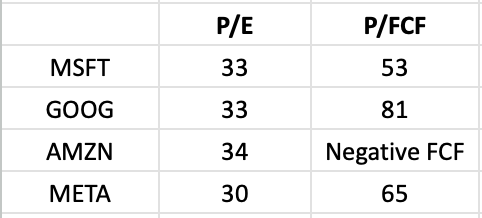

Closing this gap hinges on the go-forward ROIC generated on the booming capex. The problem for these now capital heavy businesses is it takes more and more capital to generate each new dollar of sales:

These companies need 5x the amount of capital to grow each new dollar of sales vs. a decade ago. In other words, ROIC’s are coming down as capex booms:

Source: Company filings, company estimates

I don’t have a lot of confidence in the returns this capex will generate long term. Buffett, the greatest investor of all time, has long lamented how hard it is to put $300 billion of cash to work just one time. Imagine putting that much to work in just 12 months, and then doing it again next year, and the year after that. Mean reversion is a 1.000 hitter when it comes to size being the anchor to investment returns.1

That said, the big tech companies have incredible core businesses and I believe that if the returns come in lower than expected, eventually they will cut back on spending. This will lead to a digestion period that will feel like a mere stomach ache for the big tech stocks but could resemble a more serious bout of food poisoning for some of the AI infrastructure companies that are currently thriving on all of this spending (datacenters, chips, memory, hardware, and other service companies helping fuel this boom).

My concern with AI stems from end user demand.

Consider the retail supply chain. A large retailer like Walmart sells products to individual customers like you and me. But Walmart has to acquire those products to sell us, which it buys from manufacturers.

An oversimplified chart that we all generally understand:

Product maker → Walmart → Individual customers

Normally there is a balanced cadence between replenishment orders (Walmart buying the product from the maker) and sell-through rates (the sale to the end customer in the store). Walmart is very smart, with sophisticated technology and a vast amount of data, which helps them accurately predict demand and how much inventory to keep in their warehouses and on their store shelves.

But sometimes, like any business, they overestimate demand. In 1996, there was high demand for a doll called Tickle Me Elmo (which has nothing to do with AI but is a fun story). Demand is an understatement. It became a frenzy. Dolls sold for over $1,000 on the secondary market (one went as high as $18,500 at an auction). Literal fights broke out between parents in the store trying to grab the last one on the shelf.

Would you fight a stranger for this?

The product sales skyrocketed in the fall of 1996, and Walmart began a massive wave of buying for the Christmas season, which promptly sold out. Walmart continued their rapid pace of replenishment into Q1, expecting demand to continue to stay high, and the doll’s manufacturer (Tyco) ramped up production. The feedback loop is very fast in retail, but for a brief period, Tyco was experiencing huge demand for their product despite end consumer demand that was no longer there.

This is a tortured analogy (and that’s being charitable), but it’s a fun memory from the 1990’s, which was around the same time that Cisco and Juniper were selling routers and switches to telecom companies who were also betting on end user demand for bandwidth. And whether you’re selling dolls, internet traffic, or GPU’s, end user demand (sell-through rates) are what matters in the end. You need cash flowing from the end customer, and I worry that the AI infrastructure industry might be stuffing the channel. There is obvious, massive demand for AI from big tech and the LLM companies, and there is fast growing demand from enterprise software companies quickly trying to retrofit their products for this new world. But my question is one or two customer layers deeper.

The recent TSMC earnings call had a quote that caught my eye:

“Our customers continue to provide us with a positive outlook. In addition, our customers’ customers who are mainly the cloud service providers are also providing strong signals… Thus, our conviction in the multi-year AI megatrend remains strong.”

TSMC’s customers are Nvidia, AMD, Broadcom and also the big tech companies like Apple and Google that design their own chips. The “customers’ customers” are the hyperscalers like Azure and AWS and the companies building the LLMs (OpenAI, Anthropic and others).

But go another layer or two (the customers’ customer’s customer, etc…)

I have a good friend at LexisNexis, a large enterprise software company that has a giant database of legal cases and court decisions that it sells via subscription to big law firms. There is an internal debate on his team right now about whether they should increase the price of their existing products (that now have AI tools) or if they should create additional add-on products. One of these paths (or a combo) is needed to justify their own investment into AI, but will the law firm customers be willing to pay more to Lexis Nexis? That question depends on if the law firm can get more clients because of AI.

The other side of the productivity coin is efficiency, and I completely believe that efficiency gains will happen, but reducing expenses only goes so far and is somewhat of a one-time event. To justify the hundreds of billions of capex, I think there likely has to be major growth in sales volumes as well.

A recent PwC survey of over 4,000 CEOs suggests the majority of companies spending on AI have not seen any benefits yet. However, it very well might be too early to tell… but something to watch.

10% Productivity Increase: the Math

It’s also hard to achieve step function changes in productivity. I heard a well-known tech titan suggest a 10% gain in productivity across the $100 trillion global economy would be easy. The S&P 500 has an operating margin of 13%. Non-technology companies average 9% The median Russell 2000 median margin is 6%. Let’s assume a 10% average operating margin for simple math: $100 of sales, $90 costs, $10 profit. This means that for every dollar of input costs, the company generates $1.11 of sales volume. Now, assume this company gets a 10% increase in productivity. The $1.11 goes to $1.22 of sales per dollar of inputs. This might mean either $110 of sales and the same $90 of costs, or the same $100 of sales and $82 of costs (or a combo of both). Either way, the result of a 10% bump in productivity means margins went from 10% to 18%.

This is possible at any given company, but unlikely across the economy as companies will compete with each other. A margin that just went from 10% to 18% might see a competitor be willing to lower prices to accept 16%, followed by a response from another competitor to 14%, and then to 12%, etc.. after all, that’s still a 20% increase in profits from where we were before. Most major technology innovations are a tailwind to productivity but most of the benefits accrue to customers in the form of lower prices. Step function changes across the economy in the form of 80% greater profits are unlikely.

Shortages and Gluts

“This unprecedented demand created a fiber shortage in 1999 that will continue through 2000. Fiber supply will continue to be tight in 2001.” - Lightwave, July 2000

A lot of people talk about the similarities to the late 1990’s telecom boom. I think there are major differences, but one similarity I do see is that companies then, just as today, talked about shortages and demand growth as if they were structural, or at least long lasting.

JDS Uniphase paid $41 billion (which used to be real money!) on a company called SDL in July 2000, citing “insatiable” demand for bandwidth. They believed the shortage of their products was a permanent feature of the new economy. Analysts argued that for every $1 spent on JDSU lasers, carriers would earn $10 in bandwidth revenue (a similar multiplier effect is used today to justify the skyhigh price of GPU’s). These fundamentals might be true at a point in time, but the conditions that permit those fundamentals aren’t necessarily permanent, and they can change far more quickly than investors expect. Within a year of that acquisition, JDS took a $45 billion writedown as the shortage turned to a glut. It was the largest writedown in history at the time.

In February 2000 earnings call, Cisco CEO said “demand for Cisco products is at record levels… our biggest challenge is simply keeping up with the order flow”. Cisco’s stock hit an all time high, and business never looked better, but months later, the shortage turned to a glut, far more quickly than anyone would have expected. It’s hard to know when the tide turns, but it can come quickly.

AI Power Demand

Today, people talk about power as the binding constraint on AI supply, but this shortage will too be solved, and perhaps is already less of a shortage than we might realize. Tracy Alloway had a very interesting Odd Lots post the other day that cited a study that looked at all the incremental expected demand coming from datacenters through 2030 (59 GW of new incoming power demand) and compared that to the planned expansion for power from the utility companies themselves (112 GW of new incoming power supply), or nearly twice as much supply as the expected increase in demand: a mismatch that would alleviate the shortage and might even resemble a glut. More notes here.

I’m not sure how these shortages get resolved, but one thing I know from studying business cycles and market history is that shortages always have a way of correcting themselves, regardless of how capital intensive or logistically difficult. This is because shortages mean excess profits are being left on the table.

Why Do “All Shortages End in Gluts”?

Every time you see the word shortage, replace it with “available profits missed out on”. Everytime you see supply, think “people with money”. When there are profits being missed out on, people with money see this and bring those resources in an attempt to grab some of those profits. This is why there is validity to the well known quote “all shortages end in gluts”. People with money (investors and businesses motivated to make money) come into the market, add capacity, grab those available profits until all of the profits are gone. Like the parents fighting over the last Tickle-me-Elmo, what’s left after all the profits are taken are just people with money, still trying to go after profits that are no longer there. This is called a glut.

Oil, railroads, electricity, autos, radio, air travel, telecom, networking equipment, bandwidth, housing, shale oil were all fast growing industries at one time. All of these markets have experienced shortages at times (available profits), which leads to investment (from the people with money), which eventually ends the shortage.

During Covid, we saw all kinds of shortages large and small: masks, toilet paper, Clorox wipes, furniture, whisky, lumber, decking, pools, boats, housing, Amazon warehouse capacity, fiscally responsible politicians, and more. All of these areas (except the last category which remains in short supply) have normalized or flipped to excess supply. I misjudged a few of these shortages myself during that time, but the lesson was valuable: there will always be enough supply (people with money) eventually. Sometimes this happens almost instantly (like when an army of Etsy sellers stepped in to capture profits selling masks), and sometimes this takes much longer, like the new home market, which was tight for years but is now sitting on more inventory than at any other time since 2007.

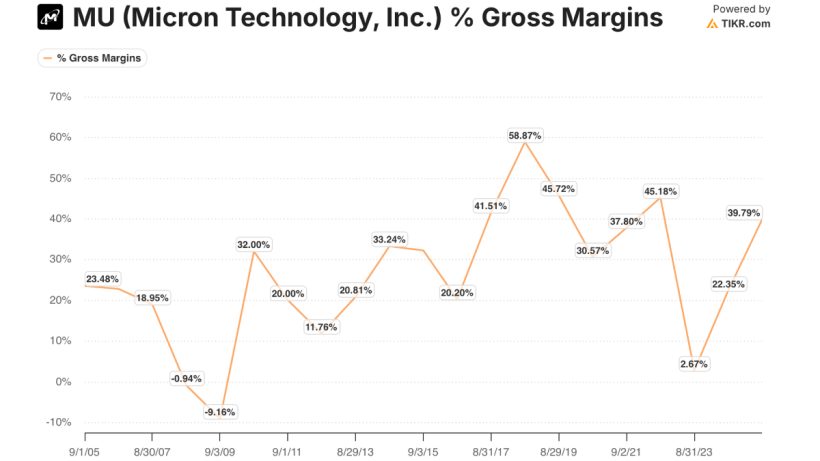

Currently, the shortage might be in power, or in memory chips, GPU’s and other related ingredients needed to build out AI. But these shortages will not last and given the amount of money entering this industry, I believe they likely will become gluts. I saw two articles this week highlighting Micron’s big push into expanding capacity, which is one of the most cyclical companies I’ve studied, as evidenced by the large range in gross margins:

To be clear, Micron has an enviable competitive position as one of only a few scaled players in the industry. Smart investors (e.g. Li Lu) have liked this stock, and I also have close friends who I greatly respect who own this (and have probably made a small fortune on this year’s appreciate alone). I don’t have a view on Micron per se, but just a general concern about shortages turning to gluts.

Unfortunately, I don’t have a good sense for the “when” on any of this. Timing markets is not a game I play, and the risk is that these stocks start turning lower well before the fundamentals are clearly recognized, so I’ll be watching things unfold from the sidelines, preferring to look for easier hurdles.

I’ll have a post later this week with a few of these easier hurdles that are currently on my desk. The good news is that opportunities abound. I think that anytime capital gets increasingly concentrated in one specific area, it often leads to an imbalance, like when too much weight gets shifted to one side of the row boat. I see an imbalance right now in how capital is being allocated within large companies and also within the stock market, and these imbalances create opportunities for stock pickers, so I think it’s a good time to be one.

I appreciate you reading, and feel free to comment with any thoughts.

About John Huber

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber manages an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.